By Meredith Sabini, Ph.D.

The last two issues of DreamTime contained a number of articles and letters on the theme of dreamwork and shamanism, with observations about their areas of overlap, similarities, and differences. It was reading these thought-provoking pieces that led me to re-evaluate my dreamwork practices and discern a shamanic element in some of them. In this column, I will describe three modes of re-telling dreams for the dreamer that I have used, one of which resembles the shaman’s tendency to take on the suffering of the patient.

Shamanism is not a religion per se but a term that refers to the body of healing practices found in indigenous cultures, including the way healers are trained. The cross-cultural features of shamanic training and practice have been identified by anthropologists and are well documented in that literature. One universal feature is that indigenous healers tend to work with dreams more consistently than do practitioners in contemporary Western healing professions, though interpretation of dreams varies significantly from one indigenous society to another. In fact, interpretation is highly dependent upon cultural variables.

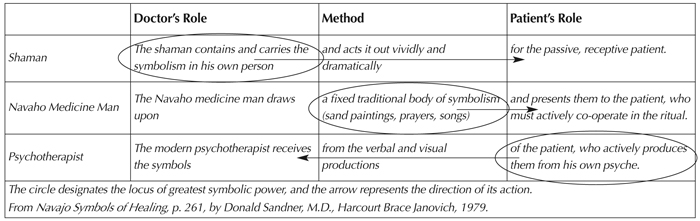

In my forties, I had a dream that I was going to attend classes on shamanism that began at 2 p.m. This suggested that some type of training in shamanism would take place in the “afternoon” of my life. It did come to pass that throughout the 1990s, a protracted initiation did take place in the classic manner whereby the instruction, mentoring, and testing occur in the interior realm known as the dream world. The experience included not only dreams in the ordinary sense, but also lucidity, out of body traveling, and encounters with spirit beings. A Jungian analyst who helped me to understand and integrate this unusual process was Dr. Donald Sandner, who himself had apprenticed with a Navajo medicine man for over a decade and traveled extensively in shamanic cultures. His book, Navajo Symbols of Healing, contains a wonderful diagram of how modern and indigenous healing differs, which I think will be of interest to anyone doing dreamwork. It is reproduced here (Harcourt Brace, 1979, p. 261).

I mention this aspect of my own background to emphasize that shamanism came to me, emerging from a non-ego source. Although I was familiar with it from having minored in anthropology in graduate school, I was not seeking this training and, in fact, have always felt very uncomfortable about Anglos appropriating indigenous traditions of any kind. What I came to realize was that shamanism seems to be arising spontaneously in the psyches of modern persons who, like myself, have a natural propensity to work as healers in this more intensely active modality. This is, I believe, a crucial point, and in the story that follows, you will see how a shamanic style of doing dreamwork gradually emerged on its own. Shamanism, it turns out, is not only alive cross culturally but is an ever-present archetypal dynamic.

I mention this aspect of my own background to emphasize that shamanism came to me, emerging from a non-ego source. Although I was familiar with it from having minored in anthropology in graduate school, I was not seeking this training and, in fact, have always felt very uncomfortable about Anglos appropriating indigenous traditions of any kind. What I came to realize was that shamanism seems to be arising spontaneously in the psyches of modern persons who, like myself, have a natural propensity to work as healers in this more intensely active modality. This is, I believe, a crucial point, and in the story that follows, you will see how a shamanic style of doing dreamwork gradually emerged on its own. Shamanism, it turns out, is not only alive cross culturally but is an ever-present archetypal dynamic.

Like shamanism, dreamwork is not one thing but varies from region to region, practitioner to practitioner. And though dreamwork is not necessarily shamanic, it may resemble some shamanic practices in tenor and effect. This came to be the case with the re-telling of a client’s dream, a practice that began as a very ordinary part of how I worked.

The Ordinary Voice

From early in my career as a psychologist, I would ask clients for dreams, then write them down during the session and repeat the dream back to the client to make sure I had it right. I invited them to add to or correct what they heard. For a long time, I thought of this as merely a perfunctory step to be gone through, after which the more important, more meaningful exploration of the dream would commence. With experience, I came to realize that this interchange of telling and re-telling the dream was in and of itself the initial phase of mutually-engaged dreamwork.

Clients have never heard their own dream. It can be eye-opening to just sit and listen to it. This step by itself often evokes comments, emotional reactions, and connective associations from the client. The dreamworker or therapist need not lead the way when the re-telling sets off sparks. The dream has become the “third thing” in the room, with both parties having spoken it and heard it.

The Dramatic Voice

At one point in my career, I began giving more public lectures, and for this I got voice training from an acting coach. She taught me how it was possible to speak more loudly and clearly without opening one’s mouth wide or shouting. As this mode of speaking, where the voice is seen as an instrument one plays, became more natural to me, I found myself using it at times as I read dreams back to clients. It was with this step in my own development that I realized I was giving clients something they had never had: the gift of hearing their own dreams. This aspect of the dreamwork was no longer perfunctory, but filled out and took on more vitality. I introduced the practice by saying that hearing their own dream was probably something that had never happened, that it was a unique opportunity to be a witness to the creative unconscious. By framing it this way, I was inviting clients to treat their own dream more objectively. I also found myself saying, “If this were someone else’s dream, what would you think of it? How does it strike you?” By repeating their dream with a full voice, I freed the client from being unconsciously immersed in the dream experience, so that they could observe it for the first time.

The potency of this method was brought home to me one day by the reaction a colleague had to hearing her own dream spoken aloud. She was a somatic therapist with whom I occasionally traded services: an hour of her excellent deep tissue work for an hour of dream consultation. She was in her fifties, had previously been in long-term psychotherapy, and was experienced in working with dreams. The dream she told that day concerned an outing with her family of origin. I was puzzled as I listened to it, for it contained no noticeable conflict, tension, or problem. But I wrote it down and, with no goal in mind other than clarifying the sequence and details, I repeated it back to her, telling her I would do this so she could hear and correct it. When I finished reading the dream from my notes, she appeared stunned, and then began to weep copiously, which took her and me by surprise. The dream, she said, showed her father doing something that, in the entire history of their family, he had never done: initiating a family outing and treating them to dinner. In one simple episode, the dream captured a central loss in her personal history, which she could now reflect on with full mature feeling. When our time neared the end, she told me that it was the hearing of her dream, and this alone, that elicited the whole range of its implications. She thanked me profoundly for re-telling it with vim and vigor.

The Shamanic Voice

When we are the dreamer telling a dream, we may feel reluctant to fully embody affective states that are present, and may dampen down the fear, anger, aggression, or sexuality present. Dream theater techniques enable people other than the dreamer to embody figures in a dream; this frees the dreamer to watch the narrative as others carry the felt and unfelt emotions and conflicts.

There is research suggesting that therapists of the introverted intuitive typology may temporarily experience a patient’s psychosomatic symptoms—headache, nausea, or specific pain—without knowing where it is coming from. In shamanic traditions, this phenomenon is well known and expected: the medicine person intentionally takes on the illness of the individual seeking their help, and in this way, knows what ails the seeker and what the cure might be. A trained shaman knows how to enter states of merger thoroughly, and come out again.

When I re-tell a client’s dream using a dramatic voice, as an actor might, I nevertheless stay true to the dream’s text; it is like a staged reading, moving and perhaps evocative, but the dream remains the dreamer’s. I recently noticed that there are other times when I move more fully into the dream myself. It may be more accurate to say that the dream moves into me and works on me, as if it becomes my dream. A merger takes place and I let myself go into the unknown. An abaissement du niveau mental or lessening of the conscious mind occurs so that the creative unconscious is present. What I repeat in the re-telling will be the dream I heard, but the emphasis may shift. As I embody the feeling states in the dream, I may bring something forth that was hidden or overlooked; I may emphasize a certain phrase or scene that was not emphasized in the dreamer’s rendition.

Recently, in a dream group I do for therapists, I re-told one participant’s dream and then repeated a particular phrase, almost chanting it: “I’m giving things away.” This had a quasi-hypnotic effect on the dreamer, whose jaw dropped as she recognized its significance as a central metaphor in her life. I then repeated, chant-like, another phrase from the dream that was less obvious: “I’m holding onto what I have.” These polar opposites were cast in relief, revealing the lifelong tension between self-sacrifice and serving the Self. The dreamer was at the point in later life of making the shift from the former to the latter. My pulling out these phrases from the dream as I re-told it provided a koan for her to meditate on.

Summary

I have described three modes of re-telling dreams for the dreamer. The ordinary voice is usable by anyone doing dreamwork and can be done at any point, including the first session. The dramatic voice can be used by anyone with drama training or a natural flair for acting; it is more appropriate in an ongoing dream group or with established clients. Re-telling a dream in a shamanic or oracular voice would occur naturally when one has relevant training and experience, and would probably be used only with clients one knows well.

With each of these voices, it is important to let the client know that you’d like to repeat their dream, and for what purpose; you may wish to ask permission and explain the benefits. Using our ordinary speaking voice to re-tell a dream does not constitute a ritual, which is a set of culturally sanctioned behaviors specifically out of the ordinary for an agreed upon purpose. When the dramatic voice or shamanic mode is used in dreamwork, this could constitute a ritual, in that the endeavor takes all parties out of the quotidian and opens to nonordinary reality, however briefly. Our modern Western culture is sadly bereft of rituals of all kinds, and the introduction of ritual forms into dreamwork would potentially lend it depth and breadth.

Meredith Sabini, Ph.D., Director, The Dream Institute of Northern California, 1672 University Ave., Berkeley, CA 94703, dreaminstituteca@gmail.com